The SAR Wall Inside Prison

Outside, an email; inside, nine lines of deterrence before you even start. By

Reece Aspinall

11/27/2023

Subject access requests (SARs) are meant to be simple. Outside prison, most of us can fire one off in minutes: copy and paste a template, fix typos with spellcheck, and send it by email. The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) even provides public guidance and a tool that can generate an email request once you enter the basics.

Inside prison, the same legal right hits a practical wall.

Under the Ministry of Justice’s own published “personal information charter”, people asking for their prison or probation data can write to the Branston Registry, Building 16, S & T Store, Burton Road, Branston, Burton-on-Trent, Staffordshire, DE14 3EG. The address is also used in prison and probation information-request guidance circulated to prisoners.

In prison-facing guidance, it is sometimes printed even longer, like this:

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE

SUBJECT ACCESS REQUEST TEAM

BRANSTON REGISTRY

BUILDING 16, NDC SITE

BURTON ROAD

BRANSTON

BURTON-ON-TRENT

STAFFORDSHIRE

DE14 3EG

That extra “SUBJECT ACCESS REQUEST TEAM” and “NDC SITE” might look harmless on a screen. On an envelope written in biro, it is another chance to make a mistake, another reason for mail to be returned, another day lost to internal post.

Count the friction. It is not one line. It is not two. It is a full block of place names, site labels and postcode, copied out by hand, usually without a keyboard, without autocorrect, and often with only limited access to stationery. The “how” matters, because the “how” decides who gets through the door.

This is not a small inconvenience. For a person on remand, time is evidence. A request delayed by weeks can mean the difference between getting disclosure in time to challenge an allegation, and walking into court blind. A SAR is not gossip: it is the record of what has been said about you, what has been logged, and what has been passed on. In the prison and probation world, those notes can shape categorisation, risk flags, licence conditions, recall decisions, and what a judge is told.

The irony is that the MoJ does not pretend the process is paper-only. It offers an online route for requesting personal information, and it lists an email address for SARs. That is normal for the public. It is not normal inside a system where the people most affected may have low literacy, may not have English as a first language, and cannot simply open a browser, search a contact page, and hit “send”.

The legal principle is supposed to run the other way. UK GDPR rules require controllers to facilitate people exercising their information rights and to communicate clearly. Yet the lived version for prisoners starts with deterrence by design: a long address, written like a small obstacle course, before the request has even been read.

What this creates is predictable. The confident, the fluent, and the well-supported push through. The rest fall off early, not because they do not have a right to their own information, but because the system makes the first step feel like paperwork punishment.

This is how power protects itself without saying it out loud. Not by banning SARs, but by adding just enough hassle that fewer people bother — especially the people who need their own records the most.

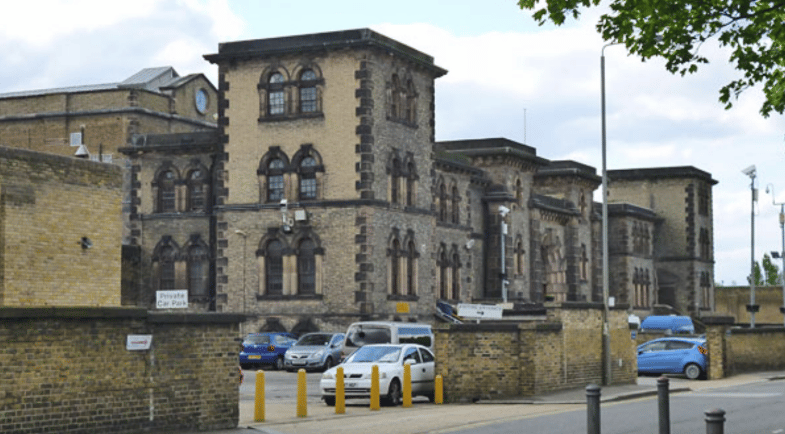

Photo credits: Wandsworth Prison (Robin Webster / Geograph), CC BY-SA 2.0; Prison Cell Door (Slingpool), CC BY-SA 3.0.

Contact

Reach out for any general questions via the email below

© 2025. All rights reserved.

To speak to somebody specifically click the button below